No products in the cart.

Calculating Maximum Pulling Tension for Fiber Cable

Home Calculating Maximum Pulling Tension for Fiber Cable

- Home

- Resource Hub

- Millennium Blog

- Calculating Maximum Pulling Tension for Fiber Cable

Installing fiber optic cable requires precision. Unlike copper wire, fiber optics are fragile. Exceeding the maximum pulling tension during installation can cause micro-bends, cracks, or complete fiber breakage. These damages often remain invisible during the pull but result in significant signal loss or network failure later. It’s important to understand calculating maximum pulling tension for fiber cable to ensure job accuracy and system security.

What Is Maximum Pulling Tension?

Maximum pulling tension defines the highest amount of force an installer can apply to a cable without damaging it. Manufacturers specify this value, and it varies significantly based on cable design. For example, a heavy-duty armored outside plant cable handles much higher tension than a delicate indoor distribution cable.

Two distinct ratings usually exist: installation tension and long-term installed tension. Installation tension allows for higher force for short periods during the pull. Long-term tension refers to the residual load on the cable after installation, which must remain much lower to prevent fiber fatigue. Installers must focus primarily on the installation tension rating during the pulling process.

How To Determine Maximum Rated Cable Load

The first step in any calculation involves consulting the cable manufacturer’s datasheet. Every fiber cable comes with a specification sheet listing the Maximum Rated Cable Load (MRCL). This value serves as the absolute ceiling for tension.

Typical values range from 600 pounds (2700 Newtons) for standard outside plant dielectric cables to shorter ranges for indoor cables. Never estimate this number. Always use the specific data for the exact cable part number slated for the project.

How Conduit Fill Ratio Affects Tension

The conduit fill ratio impacts friction, which directly increases pulling tension. The National Electrical Code (NEC) provides guidelines for conduit fill to prevent jamming and reduce drag. A lower fill ratio generally results in lower pulling tension.

When multiple cables occupy a single conduit, they can cross over each other, increasing drag significantly. Calculating the fill ratio predict how much resistance the cable will encounter. A fill ratio below 40 percent typically allows for safer pulling operations.

How To Calculate Tension for Straight Sections

Straight horizontal pulls represent the simplest calculation scenario. The tension equation for a straight section relies on the coefficient of friction and the weight of the cable. The formula is:

- T = L * w * f

In this equation, T represents the total tension, L represents the length of the conduit run in feet, w represents the weight of the cable in pounds per foot, and f represents the coefficient of friction.

The coefficient of friction depends on the conduit material and the cable jacket. Lubricants significantly lower this value. For example, pulling a polyethylene-jacketed cable through a PVC conduit with high-quality lubricant might yield a coefficient of friction around 0.15 to 0.20. Without lubricant, that number could triple.

How Bends Increase Pulling Tension

Bends in the conduit route multiply the tension rather than simply adding to it. This exponential increase makes bends the most critical factor in route planning. The formula for tension leaving a bend is:

- Tout = Tin * e^(f * a)

Here, Tout is the tension out of the bend, Tin is the tension entering the bend, e is the natural logarithm base, f is the coefficient of friction, and a is the angle of the bend in radians.

A 90 degree bend dramatically increases the load compared to a straight pull. If a route includes multiple bends, calculating the cumulative effect becomes essential. Installers should place pulling equipment or intermediate assist points strategically to manage tension through these curves.

How Elevation Changes Impact Calculations

Pulling cable vertically introduces gravity into the equation. When pulling up, the weight of the cable adds directly to the tension. When pulling down, the cable’s weight helps the pull, reducing the tension required from the winch.

For an upward pull, the formula modifies to add the weight of the vertical cable section. For downward pulls, installers must ensure the cable does not run away or exceed the minimum bend radius at the bottom of the run due to its own momentum and weight.

How To Account for Incoming Tension

Calculations must occur sequentially. The tension at the end of section one becomes the incoming tension (Tin) for section two. This cumulative effect means that a bend located at the end of a long run creates much higher tension than the same bend located near the start.

Engineers should calculate the route in both directions. Often, pulling from one end results in significantly lower total tension than pulling from the other, simply due to the placement of bends and straight sections.

How Lubrication Lowers Tension Estimates

Lubrication alters the coefficient of friction, the variable that installers can control most easily. High-performance cable lubricants reduce friction by 30 to 50 percent or more. This reduction lowers the calculated tension across the entire run.

The type of lubricant must match the cable jacket and conduit type. Using an incompatible lubricant can damage the cable jacket or dry into a glue-like substance, making future removal impossible. Manufacturers provide compatibility charts to guide this selection.

When To Use Dynamometers and Breakaway Swivels

Calculations provide a theoretical maximum, but real-world conditions vary with fiber cable pulling tension. Debris in the conduit, crushed sections, or unexpected misalignments increase drag. Installation crews use monitoring equipment to safeguard against these unknowns.

A breakaway swivel acts as a mechanical fuse. It connects between the pull rope and the cable grip. If tension exceeds the preset limit (matching the cable’s MRCL), the swivel pins shear, disconnecting the load and saving the cable.

How Equipment Selection Influences Tension

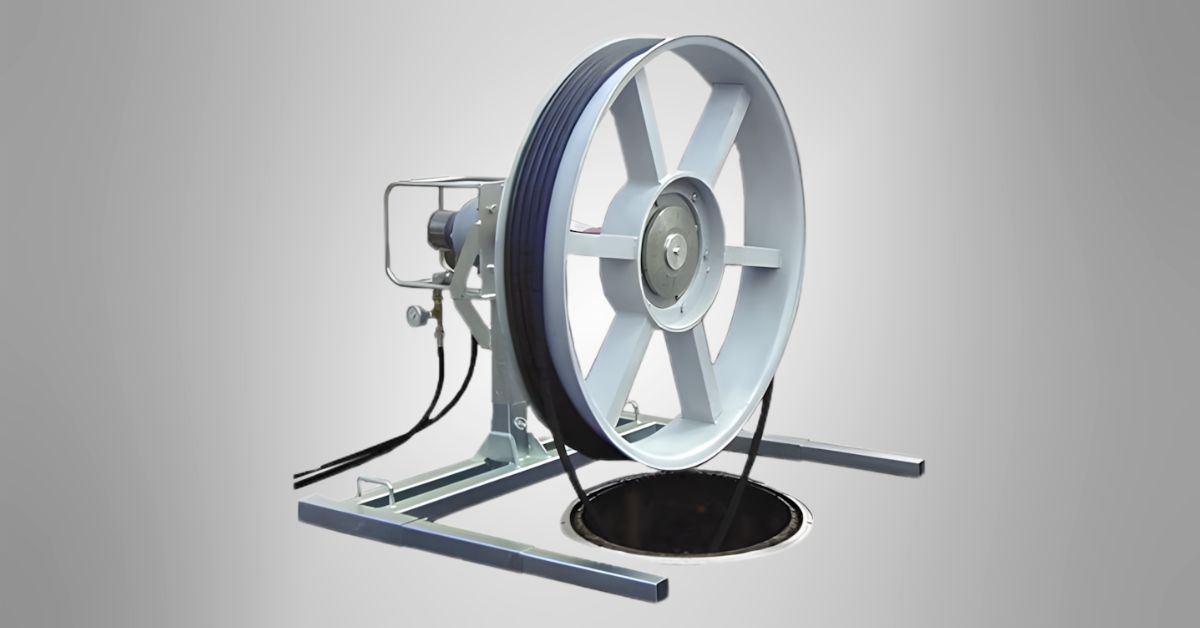

The equipment used to pull the cable affects the consistency and control of the tension applied. A manual pull by hand is inconsistent and makes monitoring difficult. Mechanical capstans or winches provide steady, controlled force.

For long or complex runs, a specialized cable pulling machine rental might offer features like tension limiters and speed controls that standard utility winches lack. These machines allow operators to set a maximum tension limit. If the resistance hits that limit, the machine stops pulling automatically, preventing damage.

The most effective way to manage pulling tension is efficient route design. Engineers should aim to minimize total degrees of bending. Instead of two 90 degree bends, a single sweeping curve or a straight path is preferable.

Millennium Broadband Solutions is a reliable partner for cable equipment and fiber network rentals. We understand the importance of ensuring accuracy and that starts with the right equipment. Let us know how we can help you.